So many interests. How do I pick just one?

How to choose your startup idea - part 1?

The a-ha series is about the moments when I felt something new. “Jot down the moments when you learn something new. And what’s really important is it’s not just about knowing something new — it’s feeling something.” — Coe Leta Stafford, IDEO

Try and fail

I’m different. I usually become curious about anything you tell me. Two years ago, I asked a few friends. Let’s start our own company?

We had four different backgrounds — Technology, Finance, Delivery, Product. Experience in Banking, Wealth, and Capital Markets. One year and 20 ideas later — from finance to transportation, health care, gig economy, even politics — we gave up.

So what happened?

- Too many interests.

- No incentive to do homework on industries out of our expertise.

- No incentive to prioritize over daily life and work.

- Fell for the myth - startup success means you do it at scale and become a billion-dollar company.

I’ll start with 1 through 3. Was it just us? Or does everybody face this? Maybe we all struggle with it? About a year later, DK asked me to do a talk. Someone asked

I’m interested in so many things. I try one, and the next, and the next - I can’t keep myself to do just a couple. Do you have any suggestions?

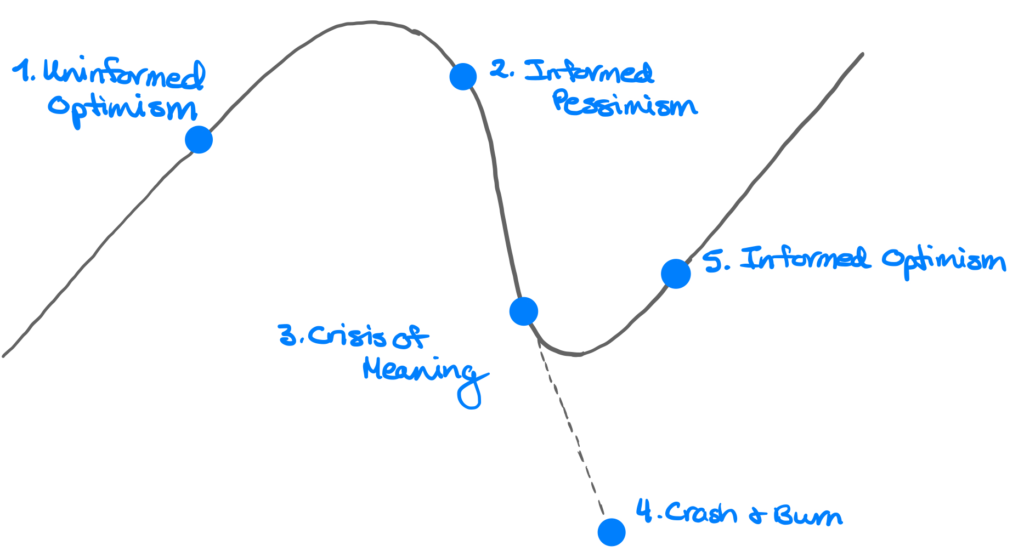

You learn over time when you think you’ve figured something out, you’ve only reached uninformed optimism.

I think I’ve figured it out, but I’ll keep reminding myself I’ve only scratched the surface.

Mixing Ikigai and human-centered design

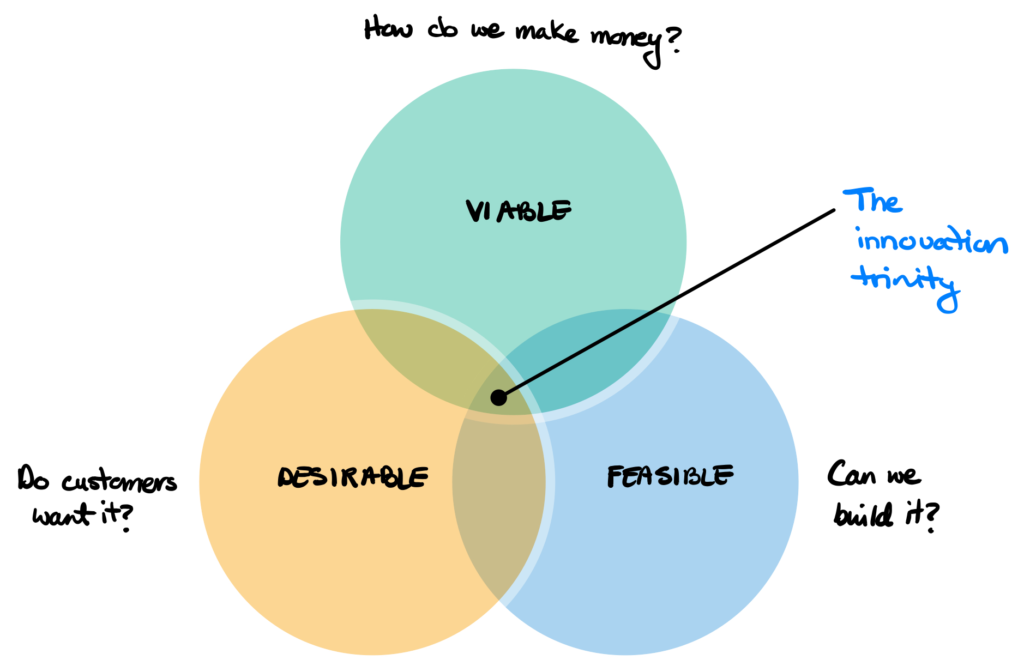

I showed our friend this idea of human-centered design:

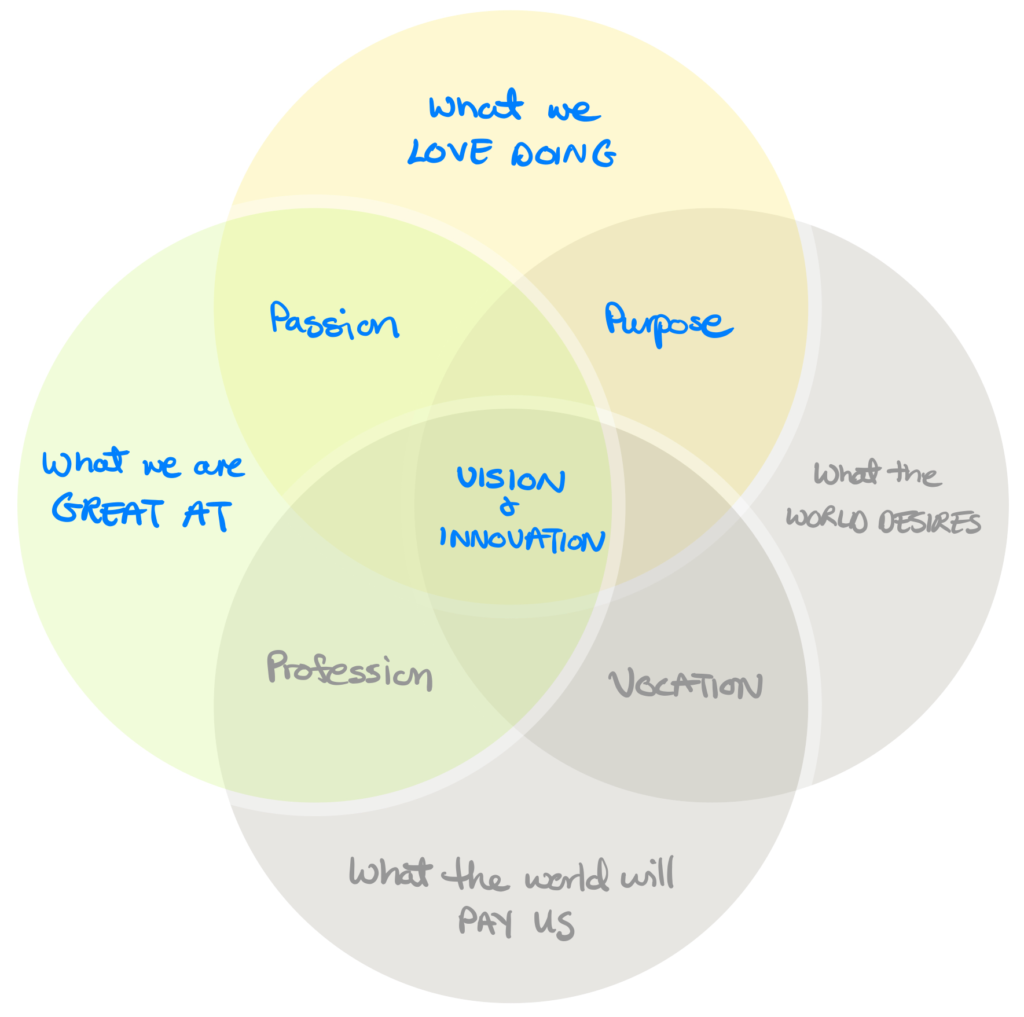

A friend told us it reminded her of “Ikigai”:

Wait! Maybe this is it. What we LOVE doing and what we are GREAT AT is how we select a startup idea:

What’s my process now?

The hardest part about starting a company is - there are no extrinsic motivators. It’s all internal motivators. Listen to [Exponent: Episode 38 — Feeds and Speeds for Life] (at 49min 5 secs) or read the excerpt:

We have two independent spectrums of factors. These tend to be extrinsic in nature, and if you lack these you experience dissatisfaction. So if you aren’t paid enough, you have poor working conditions or don’t work at a prestigious firm. If you satisfy these, it’s not that you feel satisfied. It’s that you feel an absence of dissatisfaction.

On the other end of the spectrum, you have motivators. These are more intrinsic in nature, and if you don’t have these, you don’t feel dissatisfied. There’s just an absence of satisfaction. If you do have these, you feel satisfied. And these are things like shoulder responsibility, learning, believing in what you do. — James Allworth

If there’s no money on the line, you only have internal motivators (i.e. believe in what you do) to become united around an idea.

To find yours, write your answers to

- What do you LOVE doing ー your interests?

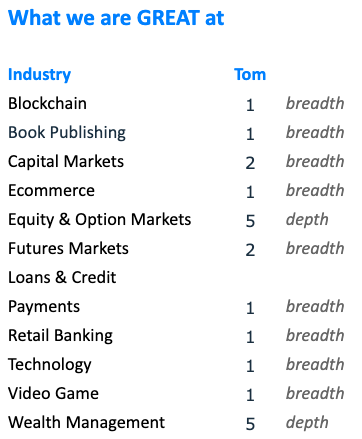

- What INDUSTRY are you an expert in — your industry strengths?

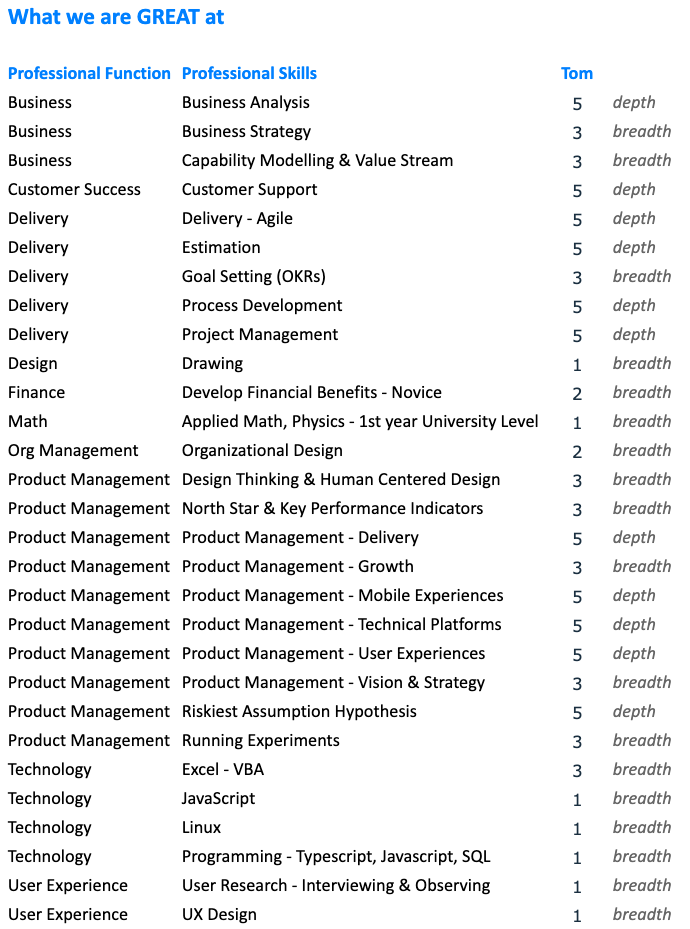

- What professional SKILLS do you have ー your functional strengths?

- Optional: Talk to people outside your team. What are their interest and strengths? Do you find it interesting - are you ready to invest time to learn it?

Peak into my internal motivators

What does it mean to be great at something?

Believable parties are those who have repeatedly and successfully accomplished something—and have great explanations for how they did it. The most believable opinions are those of people who:

- have repeatedly and successfully accomplished the thing in question, and

- have demonstrated that they can logically explain the cause-effect relationships behind their conclusions.

— Principles: Life and Work - Ray Dalio

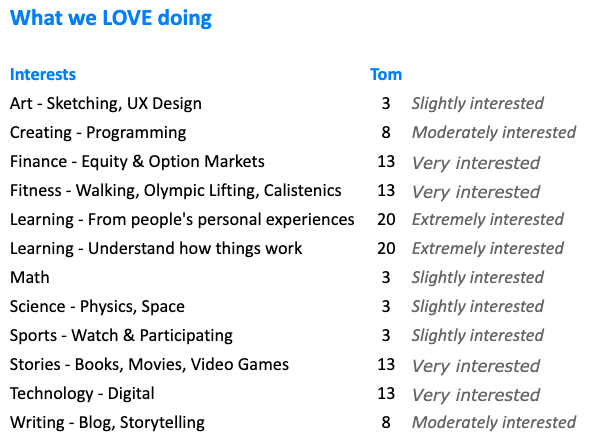

I’m a fan of relative prioritization:

- 1x — I’m barely interested

- 3x — I’m slightly interested

- 8x — I’m moderately interested (twice as interested as something at a 3)

- 13x — I’m very interested

- 20x — I’m extremely interested (twice as interested as something at a 8)

What I LOVE DOING:

What I’m GREAT AT:

- breadth of skill — can do it at novice/intermediate level.

- depth of skill — specialist in a particular craft, advanced++.

What do you love doing and are great at?

Silicon Valley has it wrong — the goal isn’t scale

Read part 2 Silicon Valley has it wrong — the goal isn’t scale.